The Price of Being Broke

How a ‘Routine’ Bond Auction Exposed the Gov’t’s Fiscal Reality (and the Fed's Stealth QE Response)

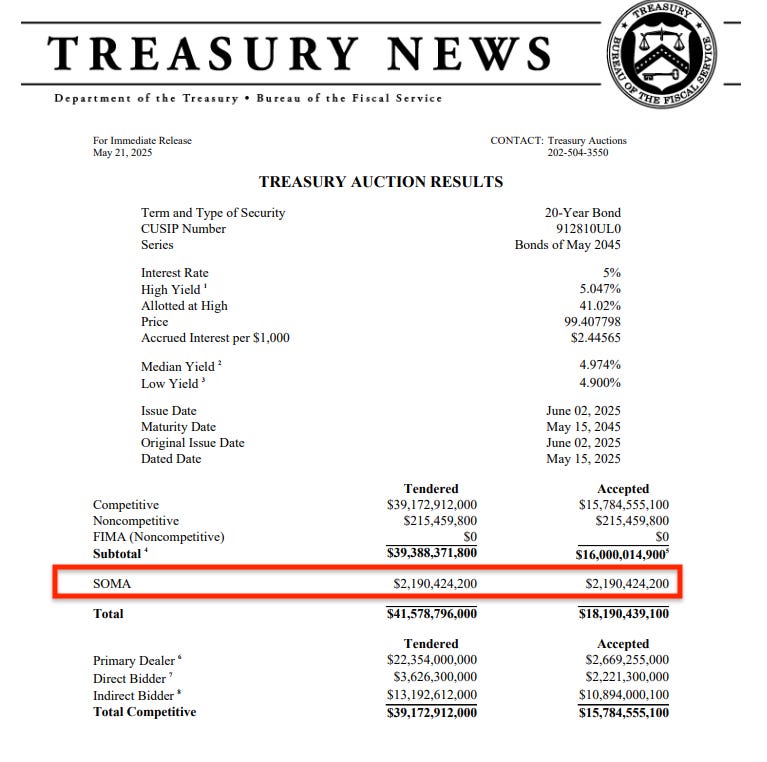

You may not know it, but something major went down last week that should have every American paying attention. On Wednesday afternoon, the U.S. government tried to borrow $16 billion through a routine Treasury auction.

But it turned into a complete disaster.

So bad, in fact, that the Federal Reserve had to quietly step in and buy $2.19 billion worth of bonds that private investors didn't want.

When They Don’t Want Your Debt

When the U.S. government needs to borrow money, the Treasury Department holds regular auctions where it sells bonds, notes, and bills to investors. It's like eBay, but instead of selling old furniture, the government is selling IOUs backed by the "full faith and credit" of the United States.

These auctions happen on a predictable schedule throughout the year, and they're usually boring affairs that markets barely notice. Investors compete to lend money to the U.S. government, which keeps interest rates low and everyone happy.

Wednesday's 20-year Treasury auction was the opposite of boring.

The bonds had to be priced to yield 5.047%—well above the expected 5.035%. That created what traders call a 1.2 basis point "tail" (basically, the extra yield the government had to offer to get the bonds sold)—the biggest since December. In fact, the government typically paid less than expected (averaging -0.4 basis points) in these 20-year auctions. Wednesday's auction flipped that script entirely—investors basically said "not so fast" and forced Uncle Sam to pay 1.2 basis points more than anticipated.

Even more troubling: the bid-to-cover ratio came in at just 2.46—the lowest since February. In plain English, that means there were only $2.46 in bids for every $1 of bonds offered. That’s a clear sign of weak demand if I’ve ever seen one.

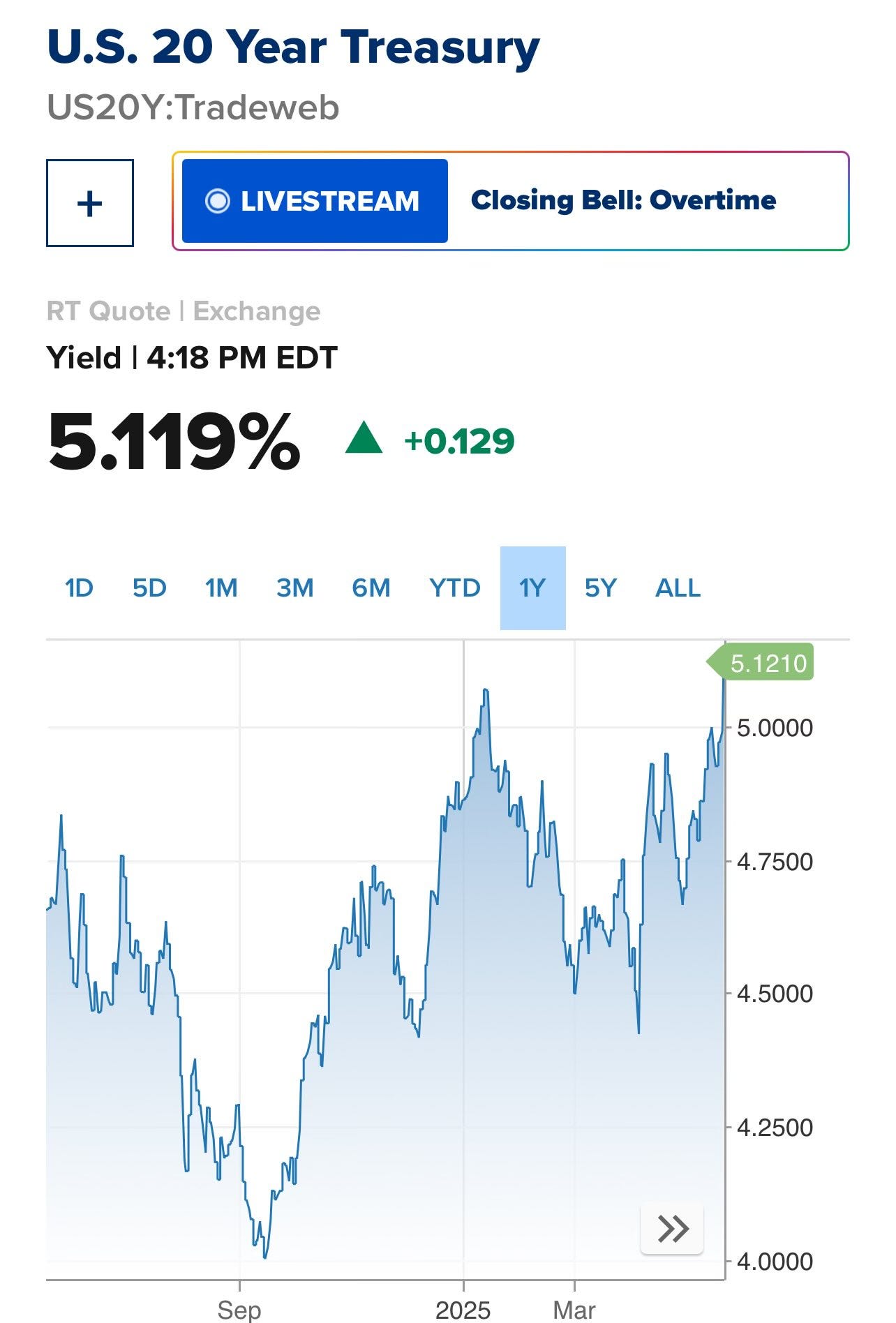

You can see the market’s reaction in the 20-year yield—it shot up past 5.1% by the end of the day, the highest level in over a year.

The 30-year bond also pushed well above the psychologically important 5% mark, and the 10-year note surged toward it. These are levels that would have been unthinkable just a few years ago.

Then came the stock selloff. The S&P 500 plunged 80 points in just 30 minutes after the auction results hit trading screens at exactly 1:00 PM ET.

It’s no mystery why.

Higher yields mean higher borrowing costs for everyone—governments, businesses, and households alike.

The Fed's Stealth QE Operation

But here's where the story gets really interesting.

Buried in Wednesday's auction results was a line item showing that the Federal Reserve's System Open Market Account (SOMA) purchased $2.19 billion of the bonds on offer.

The Fed will say this was just “routine reinvestment”—replacing bonds that matured in its portfolio. But let’s be clear: bond buying is bond buying, no matter what label you slap on it.

And then there’s the issue of timing. The Fed stepped in precisely when the auction was faltering—buying bonds at the exact moment private investors were effectively saying, “No thanks.”

And here's the other thing…

This $2.19 billion purchase wasn’t an isolated event. Just two weeks earlier, on May 8, the Fed bought another $8.8 billion in 30-year bonds. That followed a flurry of buying activity the week before, when they snapped up $34.8 billion in Treasuries. That’s roughly $45.8 billion in bond purchases in a matter of weeks—and the month isn’t even over.

To put this in perspective: the Fed's own policy states they're reducing Treasury holdings by just $5 billion per month. Yet here they are, buying nearly ten times that amount in under a month. This isn’t portfolio management—it’s stealth quantitative easing (QE), aka money printing. Plain and simple. As MarketWatch commentator Charlie Garcia put it: “It’s monetary policy on tiptoes.”

The point is, this is just another form of quantitative easing under a different name. The only difference between this and the massive QE programs of 2008–2021 is the scale and the marketing. Instead of announcing, “We’re going to buy $2 trillion in bonds,” they’re quietly stepping in—auction by auction—and calling it “portfolio management.”

What This Really Means

Whether or not you believe Trump’s Reset is unfolding as planned, one thing is clear: the appetite for U.S. debt is drying up.

If I had to guess, the Fed’s stealth QE purchases are just the beginning. It's on track to become the government's primary lender—not by design, but by default.

This is how debt crises begin. Not with headlines or crashes, but with routine interventions that turn into habits—then lifelines—until they’re the only thing keeping the system afloat.

Think I’m exaggerating?

Let’s put some numbers behind it.

In 2025 alone, the U.S. needs to borrow around $10.9 trillion. That’s not a typo.

Roughly $1.9 trillion of that is new borrowing to cover this year’s budget deficit.

The rest—about $9 trillion—is old debt that matures this year and needs to be rolled over. Most of that was issued back when interest rates were near zero. Now it’s being refinanced at over 5%.

All while the government is already spending more than $1 trillion a year on interest—more than the entire U.S. military budget.

It’s no mystery why gold is up nearly 26% this year alone. The yellow metal doesn’t lie. It’s the one asset that sees through the noise—and right now, it sees trouble coming.

Regards,

Lau Vegys

Lovely.