Our Strange Trip to Azerbaijan

We get 'Boots on the ground' where very few have ever traveled

Doug and I just returned from a trip to Azerbaijan. We were invited by our mutual German friend, Kolja Spori, who is the founder of ETIC, Extreme Travelers International Congress. It was quite a trip, and certainly I had no idea what to expect going into it.

Kolja specializes in war zones. He’s been to the Donbass a couple times. When the FARC rebel group was still active in Colombia, he visited them deep in the jungle to hear their side of the story. And our visit to Azerbaijan was focused on the former war zone contested area, the war zone between Azerbaijan and Armenia.

Americans can’t find most foreign countries on a map. Azerbaijan was obscure to even Doug and I. And yet this country played a central role in the past, and it’s clear it’ll play a central role in the future. As Michael Yon says, it’s all about routes and resources. Well, Azerbaijan has both.

From the 9th to the 16th centuries, Baku, the capital of what we now call Azerbaijan, was an important part of the Silk Road Network. Bordering the Caspian Sea, it was a crucial northern hub and crossroads which facilitated trade and cultural exchange for centuries. If you wanted to avoid the Persian Empire on the southern route for one reason or another. Or if you wanted a direct route to the Caucasus, the rising Russian principalities, or Eastern Europe - You would pass through Baku.

The Baku region also happens to be one of the most ancient and naturally oil-rich places on earth. For millennia, oil and natural gas seeped naturally to the surface through fissures in the earth. These seepages created pools of oil and eternal flames from ignited gas, which became sites of religious worship. The field of fire, a place called Yanardag, or Burning Mountain, where continuous natural fire blazes on a hillside, is a famous example that exists to this day. And long before industrial drilling, people dug shallow hand dug wells and pits to collect oil from these seepages.

The infamous incendiary weapon used by the Byzantine Empire known as Greek fire was a closely guarded state secret. Many historians believe that naptha, a highly flammable light oil from the Baku region, was a key ingredient. It was used in flamethrowers and fire pots to devastating effect against enemy ships and soldiers. While heavier oil is burned in simple amps for light, it is also used for basic heating.

As an American, I thought the modern oil industry really began in 1859 when “Colonel” Edwin Drake struck oil in Pennsylvania. It was a quintessential American story, a lone great inventor with ingenuity and grit, unlocking a new frontier and powering the country’s rise to industrial greatness. But the story of the modern oil industry had a prequel, and its setting wasn’t in Pennsylvania, but the stark, fire-scorched landscape of the Absheron Peninsula around Baku.

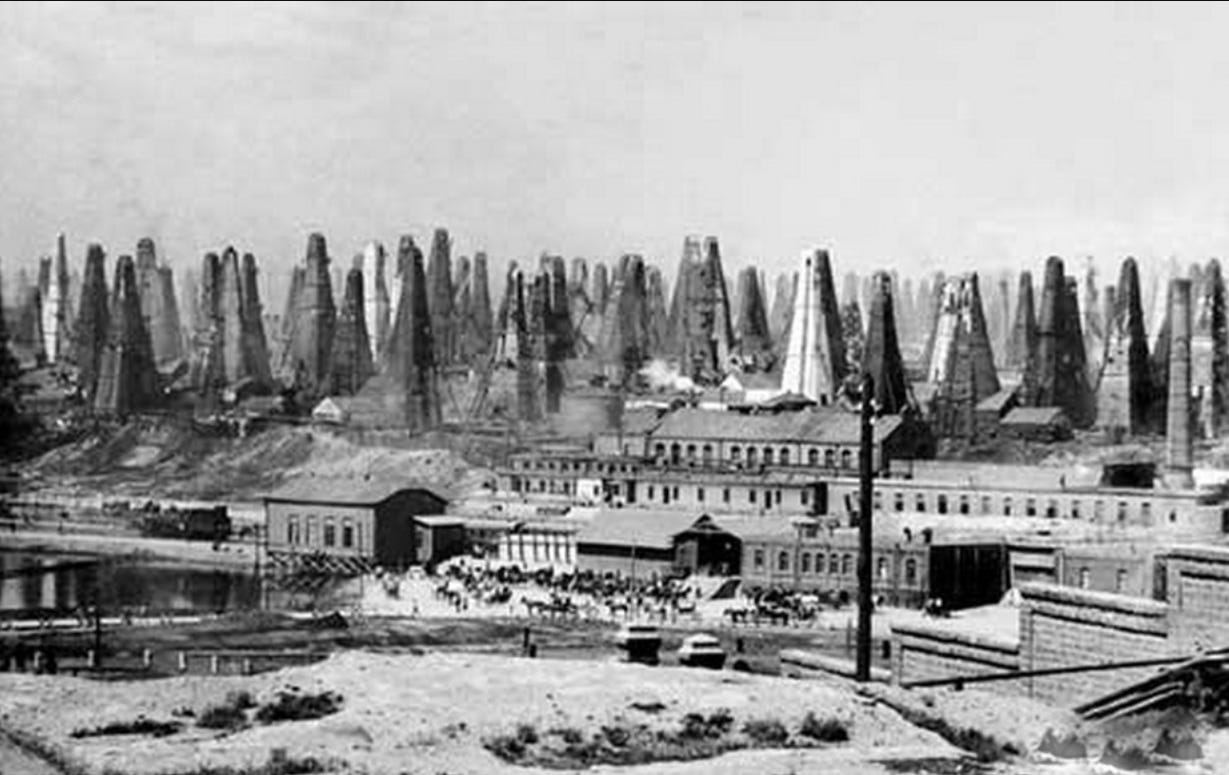

In 1846, Russian engineers successfully completed the world’s first mechanically drilled oil well near Baku. This wasn’t a lone wildcatter’s gamble. It was a state-sponsored feat of engineering that marked the true dawn of oil’s industrial age.

By the 1870s, as American fields were rapidly developing, Baku was an industrial juggernaut. The Nobel Brothers and the Rothschilds were building a vertically integrated empire of pipelines, refineries, and the world’s first oil tanker fleets. The region was producing over half of the world’s supply, lighting the lamps of Europe and Asia.

Oil is still the primary driver in Azerbaijan. It accounts for over 90% of export revenues and roughly 60% of the state budget. But the interesting thing is what they’re spending that budget on. Azerbaijan is attempting to return to its roots as a key hub in the new Silk Road.

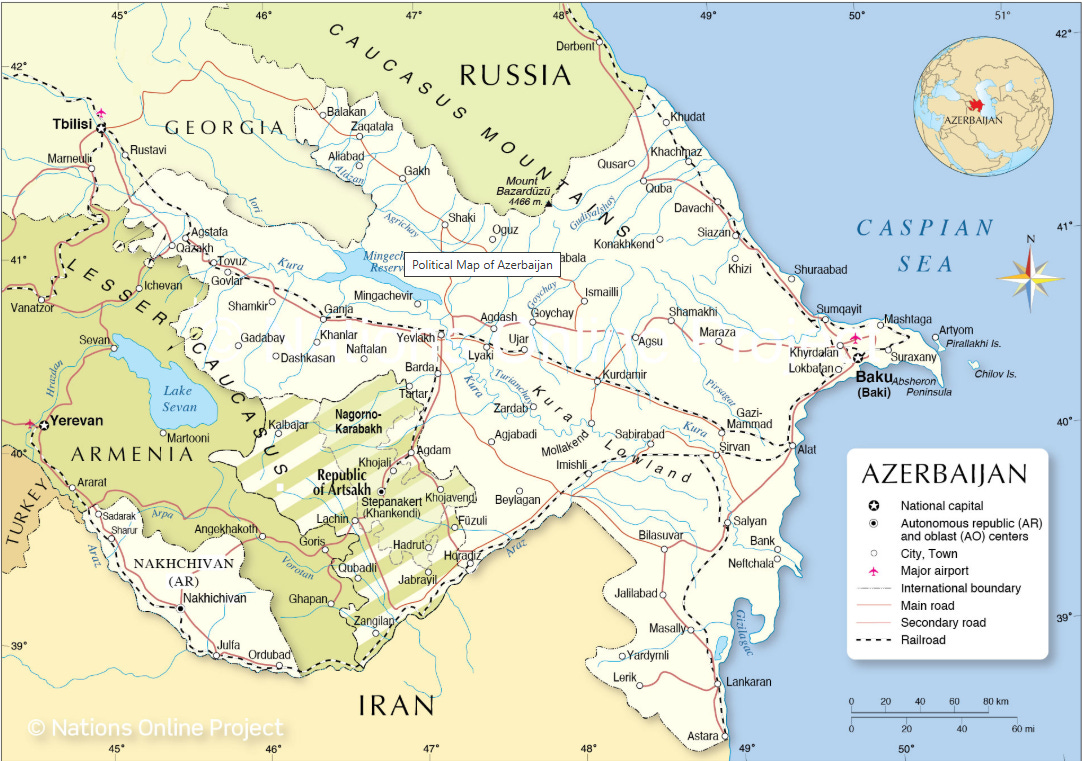

The country borders Russia to the north, Georgia to the northwest, Armenia to the west, and Iran to the south. All along the east is the Caspian Sea.

The oil business has been a great boon to Azerbaijan. But its supplies won’t last forever, and so they’re looking to the future. A future that includes, unfortunately, tourism, but also going back to its roots And becoming a key component of the new Silk Road.

Just one problem. Azerbaijan is open to the Caspian Sea and the countries beyond. But it needs access to the West, to Turkey in particular, where then its goods could flow freely from Berlin to Shanghai.

As a former Soviet Republic, when the USSR collapsed, a war erupted between Azerbaijan and Armenia, and Armenia gained control of the Nagorno-Karabakh and seven surrounding districts that Azerbaijani claimed as their own.

In 2020, Azerbaijan, using advanced drone technology from Israel and Turkey, launched a successful military offensive where it recaptured a significant portion of the seven surrounding districts and parts of the Nagorno-Karabakh itself.

In 2023, Azerbaijan launched another offensive. This military operation crushed the de facto separatist Armenian-backed government causing them to surrender and they then agreed to dissolve altogether. In the process, over 100,000 ethnic Armenians fled the region for Armenia with little more than the clothes on their backs.

There’s a lot of pride in Azerbaijan about the liberation of these territories and kicking out the ethnic Armenians. But to complete the new Silk Road, they still needed more. They need direct access to Turkey. An Azerbaijani exclave, Nakjivan, which borders Iran and Turkey, became the focal point.

In August of this year, Trump brokered a deal between Armenia and Azerbaijan where the U.S. would lease a 43-kilometer stretch of Armenian territory, allowing Azerbaijan direct access to its exclave. As part of the deal, the U.S. is responsible for overseeing the corridor’s creation and operation. The deal is supposed to end the decades-long hostility between the countries by opening this corridor and normalizing relations. For the U.S., it offers a strategic role in a region historically influenced by Russia and Iran.

The Azeris are delighted by all of this. And while we didn’t have a chance to visit Armenia, the sense I get from Armenians I do know is that the hard feelings remain, and public support of this deal is low.

It’s understandable. There’s clearly deep resentment and even hatred between almost all the Azerbaijani people we met and Armenians. And before our departure a concerned Armenian reader tried to discourage Doug from going. The Azerbaijani’s were, by his estimation, bad and dangerous people

Most of our time was spent in the Garabagh area, this recently disputed, now liberated territory where Armenians have lived for 30 years. The government has aggressive plans to resettle the area. But for most Azerbaijanis the area is off limits without special permission.

Propaganda

Every nation controls, or at least manages, its populace through propaganda. And sometimes it’s hard to see from the inside the propaganda you’re subject to. For Doug and I, the propaganda was thick and obvious, and its effect on the population very clear.

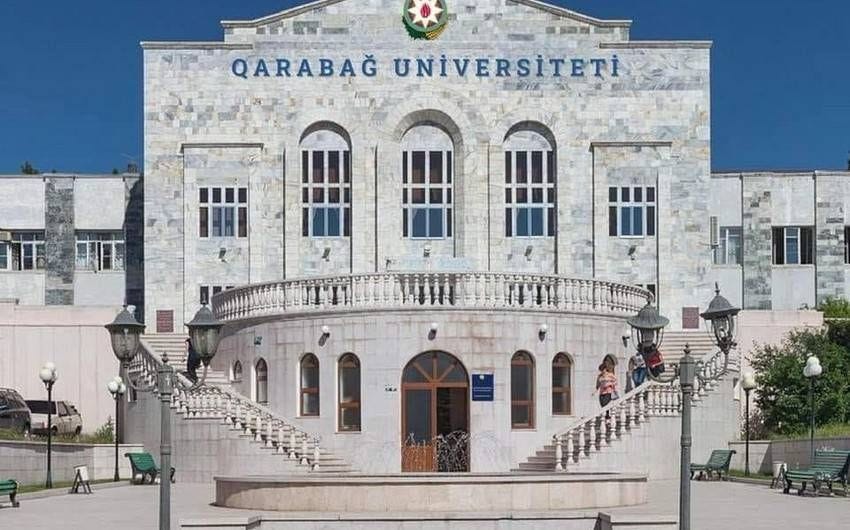

Among other things, we visited the newly opened Garabagh University. We got a tour of the university and Doug and a few other distinguished guests gave speeches to some of the faculty and hundreds of students.

We were mightily impressed by the students. They were positive, eager, welcoming, friendly, and unbelievably helpful. Doug commented that if we had visited Harvard or UCLA or any other major university in America, the tone and demeanor of the students would have been totally different and completely negative by comparison.

At the same time, it was pretty clear - the students knew we were coming. As we walked into the library, most of the seats were full of students intently writing in their notebooks. What they were writing, we have no idea, but they were clearly busy or made to look busy on our behalf.

One student, Hassan, latched on to Doug and I as we arrived and was a great help to us during our visit. He was kind and curious and extremely helpful. But at one point, when just he, Doug, and I were standing alone beneath the steps of the university, He said, out of the blue, “the Armenians are bad, very, very bad”. I looked toward him, and he went on. “They killed my brother. They killed my sister.”

“Really I asked? When?” Some of the students spoke excellent English. Hassan wasn’t one of them. So when I asked the question, he stumbled a bit. And said, “1993.”

Hassan was only 18 years old. So I said, “1993, that doesn’t make sense.” He replied, “oh, not my brother. It was my cousin. It was my cousin. So sorry. And my grandfather, too.”

At that point I looked at Doug and I said, “I think he’s speaking metaphorically.” Doug agreed.

This is the effect of propaganda on even kind-hearted Hassan. The hatred and resentment one would feel as if their brother, their sister, their cousin, and their grandfather had been murdered by some “very bad, very, very bad” group of people. And this is, no doubt, the seed of future conflict.

There was much construction in Azerbaijan. In fact, more construction than I have ever seen in my life. It’s incredible what they have done and are doing. More on that later.

But much of the construction that we saw was parks, memorials, And other reminders of the conflict everywhere you went, especially in Baku, where about a quarter of the population resides today. Every park was a memorial, a reminder of victory, or a collection of tokens of war, a war that ended just recently and are endeavoring never to forget.

The Aziris are primarily Shia Muslim, although Azerbaijan is well known to be one of the most secular Muslim nations in the world. So we saw only a few mosques, but one we did see under construction in Susha, a city of historical importance to the Azerbaijanis. And now the cultural capital of the country. Here they were building a brand new mosque, very modern looking based on the design of a church in Iceland. We were told that, when viewed from above, the mosque complex would be in the shape of an eight. Why? Because this city was liberated on the eighth day of the month. Never forget.

It struck me then that one of the great qualities of America is the ability to move on, to not hold on to these Hatfield and McCoy-like feuds that can last for generation upon generation. Doug agreed “FIFO” (Fuck it Fight on), or rather- fuck it, move on.

The propaganda didn’t end with memorials. Touring the various scenes of the recently ended conflict, it became pretty clear that we were part of the propaganda. Throughout the arduous journey through the mountains, to get to these important cities, we were tailed by a number of news reporting agencies.

Our group traveled through the area in a convoy of SUVs with a police escort most of the time. We were car number seven of eight, but apparently behind us were several cars from the press.

We went to various sites to review old villages supposedly destroyed while under occupation, we saw the new construction in these areas where the government planned to resettle the families chased out of the area more than 30 years ago.

They wanted to show us devastation and rebirth and brought us to many seemingly staged symbols of both. At these stops most of us would step out, listen to the Azeri spokesperson and take pictures. Behind us, although you might not notice unless you’re looking for it, with the press taking pictures of us.

I like to think I have good situational awareness, but I really wasn’t clued in to how clever they were until at one stop after a particularly brutal drive, Doug and I chose to sit in the car. After a moment or two, a dozen or so of these members of the press corps walked past our parked SUV and behind the other members of our group, snapping pictures. And in that moment, it was clear what was happening.

Often, these members of the press would pull one member of our group aside requesting an interview. Azerbaijani news doesn’t leak into the rest of the world. The audience is internal. And so, during these interviews, they’d ask questions about what people thought of the country, thought of what happened, their view of the future of the country, etc.

I can’t say whether all the comments, some of which must have been critical, made it into the local press, but certainly many of the useful ones did. At the end of this article, I’ll share a bunch of links, so you can check out the press reports for yourself.

Now this all sounds bad, this effort of the press. But remember, you are very much subject to the same in whatever country you live in today. Propaganda is the tool by which governments manage, if not control, their people. You included. Remember 9/11? How about the 30.06 used to assassinate Charlie Kirk?

CONSTRUCTION

By far, the most impressive thing I saw during our visit was the level of construction occurring in the country, and in particular within the formerly disputed territories, the scale of which is almost beyond imagination.

We traveled a brutal route to Garbaragh on the older roads through very rough mountain terrain. But occasionally I could glimpse below in the valley a brand new highway system which included dozens of tunnels. Now this is probably the most difficult terrain possible to do major construction. And yet what I glimpsed from above was shocking in scale.

And even along the roads that we traveled, there were endless streams of heavy equipment, hard at work, reshaping the landscape to expand the highway system we were on. There were cement factories everywhere built bespoke to support this ambitious effort.

The scale was so massive, so inorganic, and so out of place, we had a hard time making sense of it. To do something like this in America would be utterly impossible. It would cost trillions of dollars. The thinking required, too big, the manpower, unavailable, the will, long gone. But here in this little country, nobody knows anything about it was happening.

I knew it was an oil-rich country, but still, thinking in American terms, and seeing this scale of construction, the costs I imagined seemed utterly impossible. And so, at my earliest opportunity, I did some research. What I found was shocking.

The country is only about the size of Connecticut. So you have to put that in perspective. But for 2% of America’s annual budget for highways and bridges, viaducts, and infrastructure like that, Azerbaijan had built 4,000 kilometers of highway, 45 tunnels, including the second longest in the world, 447 bridges, 16 viaducts. Much of this over very, very difficult terrain. The project was mostly complete. And the total project time was less than five years.

All this they’re doing for approximately $5 billion. To put that in perspective, on March 26, 2024, the Francis Scott Key Bridge in Baltimore was damaged when a container ship collided into it.

As of today, the bridge stands unusable. No repair work has yet started. The estimated cost for reconstruction of that bridge is between $1.7 billion and $1.9 billion. And when will it be done? It hasn’t even started yet. The current target completion date is October 2028.

So, in four and a half years, and for about $2 billion, we get an old and important bridge replaced in one of America’s cities. And in Azerbaijan, for $5 billion, they get 447 bridges, 4,000 kilometers of highways, dozens of tunnels including the second longest tunnel in the world. All in less than five years.

If you know anything about China, it’s hard not to be blown away by the scale and quality of construction that’s been happening there these last several years. But it’s easy to excuse it away and say, well, that’s China. There’s something different happening there. Maybe it’s the population or slave wages. Maybe it’s the government. Maybe the stats aren’t right. Maybe it’s terrible construction. These are the excuses we Americans use to justify what we see there.

But this is Azerbaijan. What possible advantages do they have over America that enable them to produce such amazing infrastructure at such low cost and in so little time?

Perhaps a better question is what is wrong with America? Each year we spend about $250 billion on roads, bridges, and infrastructure. And yet the American experience, certainly the experience of my lifetime, is highways decaying, construction never ending, miles of orange cones everywhere, and years passing by with no visible improvement around you.

Something is deeply wrong with America, and it extends beyond our decaying infrastructure. When we ask the locals if they were optimistic about the future, the uniform answer was yes. And as you look at all of the construction improvements, the massive and rapid visible improvements in the physical surroundings, they see progress. They feel the improvements, and they can see that the future is getting better by the day.

Contrast that with the good old USA, where year by year we witnessed decline, decay, impotent efforts at improvement, failed plans for new infrastructure. Looking at our physical surroundings, we have seen firsthand, the future means decay not advancement.

How can we not be pessimistic about the future?

Something is wrong with America and it’s not just regulations or corruption. Most of those exist everywhere. America’s thinking has become too small, too shortsighted. It seems we lost the will to build at scale. Once the will was gone, the competency fell away too.

Before coming here, I really couldn’t grasp the great innovative powers America had lost, the powers that allowed us to build the Empire State building in record time, to construct the national interstate system, the golden gate bridge, to build up great new cities from former prairies. All of that happened before I was born.

But I can see it now and it’s far worse than I thought.

Best,

Matt Smith

P.S. Here’s a list of local news reports generated from our visit.

https://report.az/ru/karabakh/mezhdunarodnye-puteshestvenniki-oznakomilas-s-razrusheniyami-v-agdame

https://report.az/ru/karabakh/puteshestvennik-iz-portugalii-v-karabahe-lyudi-nakonec-zhivut-v-mire

https://apa.az/turizm/alman-seyyah-agdamda-fantastik-isler-gorulur-922651

https://apa.az/turizm/beynelxalq-seyyahlar-xankendiye-sefer-edib-video-922693

https://azertag.az/xeber/dunya_seyyahlari_qarabag_universitetinde-3818199

https://azertag.az/xeber/beynelxalq_seyyahlar_lachinda-3818903

https://apa.az/turizm/beynelxalq-seyyahlar-lacina-sefer-edib-foto-yenilenib-922766

https://report.az/en/other/etic-member-global-media-covered-azerbaijan-biasedly-for-decades

https://www.trend.az/azerbaijan/society/4108472.html

https://www.oananews.org/node/707078

https://www.trend.az/azerbaijan/society/4107106.html

https://azertag.az/xeber/dunya_seyyahlari_agdamda_tarixi_mekanlari_ziyaret_edibler_yenilenib-3817367

https://azertag.az/xeber/dunya_seyyahlari_qarabag_universitetinde-3818199

https://azertag.az/xeber/beynelxalq_seyyahlar_lachinda-3818903

https://azertag.az/xeber/dunya_seyyahlari_susada_tarixi_abideleri_ziyaret_edibler-3819827

https://report.az/xarici-siyaset/xarici-qonaqlar-qarabag-universitetini-ziyaret-edibler

https://report.az/xarici-siyaset/teskilatci-qarabaga-indiye-kimi-600-den-cox-seyahetci-sefer-edib

https://report.az/qarabag/beynelxalq-seyyahlardan-ibaret-novbeti-qrupun-qarabaga-seferi-baslayir

https://report.az/qarabag/dunyanin-meshur-seyyahlari-agdama-gelibler

https://report.az/qarabag/portuqaliyali-seyyah-qarabagda-insanlar-nehayet-sulh-icinde-yasayir

https://report.az/qarabag/beynelxalq-seyyahlar-agdamdaki-dagintilarla-tanis-olublar

https://report.az/diger-olkeler/sekkiz-olkeden-olan-seyyahlar-xankendiye-gelibler

https://report.az/xarici-siyaset/xarici-qonaqlar-qarabag-universitetini-ziyaret-edibler

https://report.az/qarabag/beynelxalq-seyyahlar-lacini-ziyaret-edibler

https://report.az/qarabag/beynelxalq-seyyahlar-lacinda-qalereyani-ziyaret-edibler

https://report.az/qarabag/beynelxalq-seyyahlar-susaya-gelibler

https://report.az/qarabag/beynelxalq-seyyahlar-susanin-merkezi-meydaninda-abidelere-baxiblar

https://report.az/qarabag/beynelxalq-seyyahlar-govheraga-mescidini-ziyaret-edibler

https://report.az/qarabag/sekkiz-olkenin-seyyahlari-fizuliye-gelib

https://apa.az/turizm/beynelxalq-seyyahlar-agdama-sefer-edib-foto-yenilenib-video-922635

https://apa.az/turizm/alman-seyyah-agdamda-fantastik-isler-gorulur-922651

https://apa.az/turizm/alman-seyyah-qarabagda-inkisafdan-cox-tesirlendim-922729

https://apa.az/turizm/beynelxalq-seyyahlar-xankendiye-sefer-edib-video-yenilenib-922693

https://apa.az/turizm/belcikali-seyyah-qarabagda-gorduklerim-meni-heyretlendirdi-922739

https://apa.az/turizm/beynelxalq-seyyahlar-lacina-sefer-edib-foto-yenilenib-922766

https://apa.az/sosial/beynelxalq-seyyahlar-susaya-sefer-edib-yenilenib-foto-922849

https://apa.az/turizm/almaniyali-seyyah-umid-edirem-ki-sulh-berqerar-olacaq-922922

https://apa.az/turizm/amerikali-seyyah-minatemizleme-prosesini-izlemek-heyecanli-tecrube-oldu-922930

https://az.trend.az/azerbaijan/society/4107286.html

https://az.trend.az/azerbaijan/society/4107322.html

https://az.trend.az/azerbaijan/society/4107340.html

https://az.trend.az/azerbaijan/society/4107069.html

https://az.trend.az/azerbaijan/society/4107961.html

https://az.trend.az/azerbaijan/gundem/4107747.html

https://az.trend.az/azerbaijan/society/4108471.html

https://az.trend.az/azerbaijan/society/4108511.html

https://news.day.az/azerinews/1789931.html

As others have said, thanks for a very informative & revealing article; I had no idea... All I get via western media is a filtered version of what they want me to know...what's that word again? Oh yes, propaganda.

I enjoyed this article very much. Not so much as a history lesson, just more about what is going on around the world that most don't know or care about. There are pockets of conflicts everywhere...some well known and others not-so-much or completely forgotten about that continue to simmer away until some future boiling point. Back to Azerbaijan, I though I would include this YouTube link as I am positive this man is the most famous person from there..

https://www.youtube.com/c/WILDERNESSCOOKING

PS..Matt, I bought 'The Preparation' for myself... I don't have any children of my own. However at 64, I still feel lost now as when I was Maxim's age.